A few days since my last entry. Hoping to write something that will draw disparate strings together and reference some of my earlier writing pieces. In particular, I want to write about circumlocution and add some context to how it influences my thinking today. I expect to write about this in the most mundane way possible, veering as far from theory as I can muster, out of necessity to keep things safe and tangible.

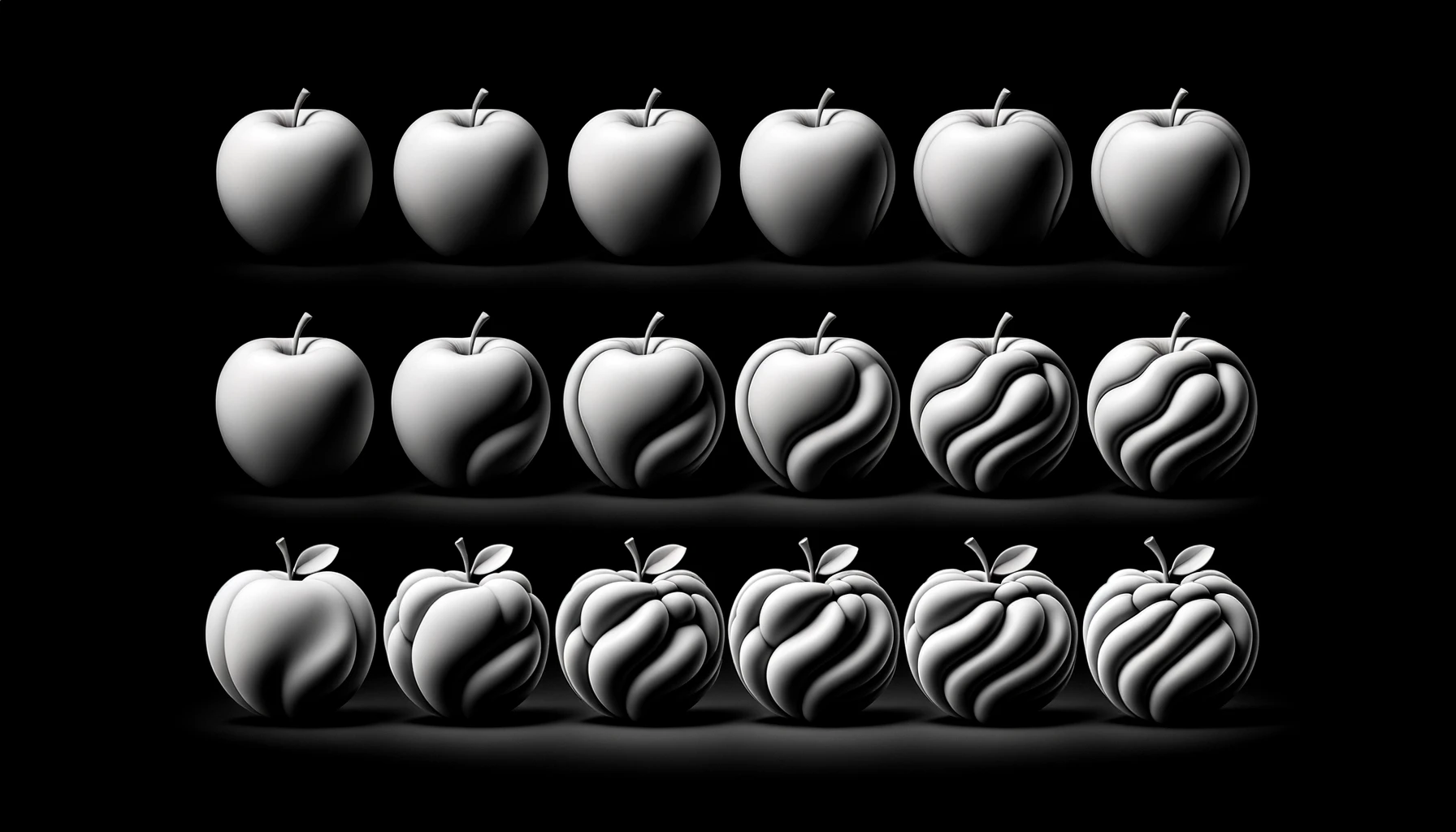

So where to begin? Symbols flow into us. Someone speaks, and this could be a speech actor, but also a visual pattern. Any maker of meaning—be it a pattern on cloth, someone speaking English, the vibrations of a speakercone emitting sound—it all passes some signal. Language models are no different, in the simple sense that they arrange and re-arrange tokens to create some comprehensible message. Even diffusion models are acting in this sense: by a process of creation they access meaningful arrangments of pixels that can become a carrier of meaning and therefore interpretable to the (mostly) human viewer. Take this example of an apple:

Here the model was asked to draw the ‘essence’ of an apple. It arranges pixels in such a way that an image appears that seems to capture some figurative notion of apple-ness. In many regard’s it’s too perfect to be an apple. The shiny gloss, the smooth shape, the way light glows off it’s edges gives a sense that while we can see the apple, it’s more so the illustration of an idea of an apple. Yet even so, the image is able to trigger something in our imagination that makes it recognizable to us. This back and forth, between image and recognition is something we’ve been perfecting in machines for years, and yet it’s a two way street. We also have been perfecting the ability to, computationally, create an order to pixels so that images will appear to us recognizable in our imagination. Indeed, it’s not merely to create an apple, but to be able to create permutations on appleness that allow us to see other visual features.

In the following AI generated image, we’ve created a spectrum from ‘Apple’ to the apple’s physical state becoming increasingly more altered and air-like. It’s a bit strange, a bit uncanny. But we recognize the transformation from pure apple, to something with the apple’s form but made out of a gaseous material. Here we encounter an encounter between the ability in the human to recognize an apple and the ability to recognize materials and gaseousness. Moreover, we find that the model is doing the same in order to produce something recognizable in us. It takes something familiar, and applies a steady transformation: first slight gas appears to emanate from the apple, and as one goes left, it increasingly transfigures into something that is representing gaseous properties.

We could go further still and take properties more emotive. Here I’ve asked it to create a spectrum from happy to sad apples:

Here we find the apple figure transformed into increasingly more disfigured shapes until finally a skull and a brooding purple apple. The discoloration on the apple’s leaves as well suggests discontent in the apple third from the left. The apples play with our perception, allowing us to see a skull morphed onto a dried up apple as some bizarre epitome of sadness. Even more uncanny may be the purple apple that follows: if death is the second most unhappy apple, is the purple apple the representation of loss and grief? Regardless, we find that each apple arranged in this way indexes upon our ability to access representations of apple and assign sentiments to them. We find in ourselves the capacity to interpret and even emotively respond to the representations of apples. Perhaps apples like the third to last instill a bit of revulsion with it’s rotten form—and maybe that was the purpose of drawing it in this way. Indeed we find a creative capacity within the image model to create increasingly more elaborate representations of sadness using the basic figure of the apple. This suggests the presence of an underlying structure which understands what visual features, in relation to apples (like rot) and otherwise (like a skull) carry with them connotations and can access an emotive response in the human viewer.

Here is another representation of happy to sad apples that is a little more sublte:

Surface patterns, color, texture, tell-tale signs of mold, all come together to create increasingly more distressing apples. We find that even in the more subtle differences between the intermediate apples there are some signs of difference that leave us wondering if those apples are indeed more sad than their neighbors. It’s not clear to me that they are, as a viewer, but at least I understand when the apple turns yellow, or begins to look increasingly more rotten. What is going on? It appears as if the model is working to satisfy the constraints of apple-ness while meeting the rest of the prompt to create increasingly more sad depictions. It reveals an ability to model apple forms and textures in such a way that makes them appear increasingly more rotten and textured while maintaining the basic structure. That it was not told to do this to the apple, but rather can infer that this will create the appearance of something more “sad” again reveals an underlying structure or model within the model to represent sadness through the constraints imposed by figure and form. Indeed here it does not disrupt our expectation of how an apple should appear by, for example, imposing a skull, but instead maintains the top-level constraint and yet can work within it.

Indeed other transformations can be imposed on the apple which reveal a facility with changing the shape and textured properties of the apple:

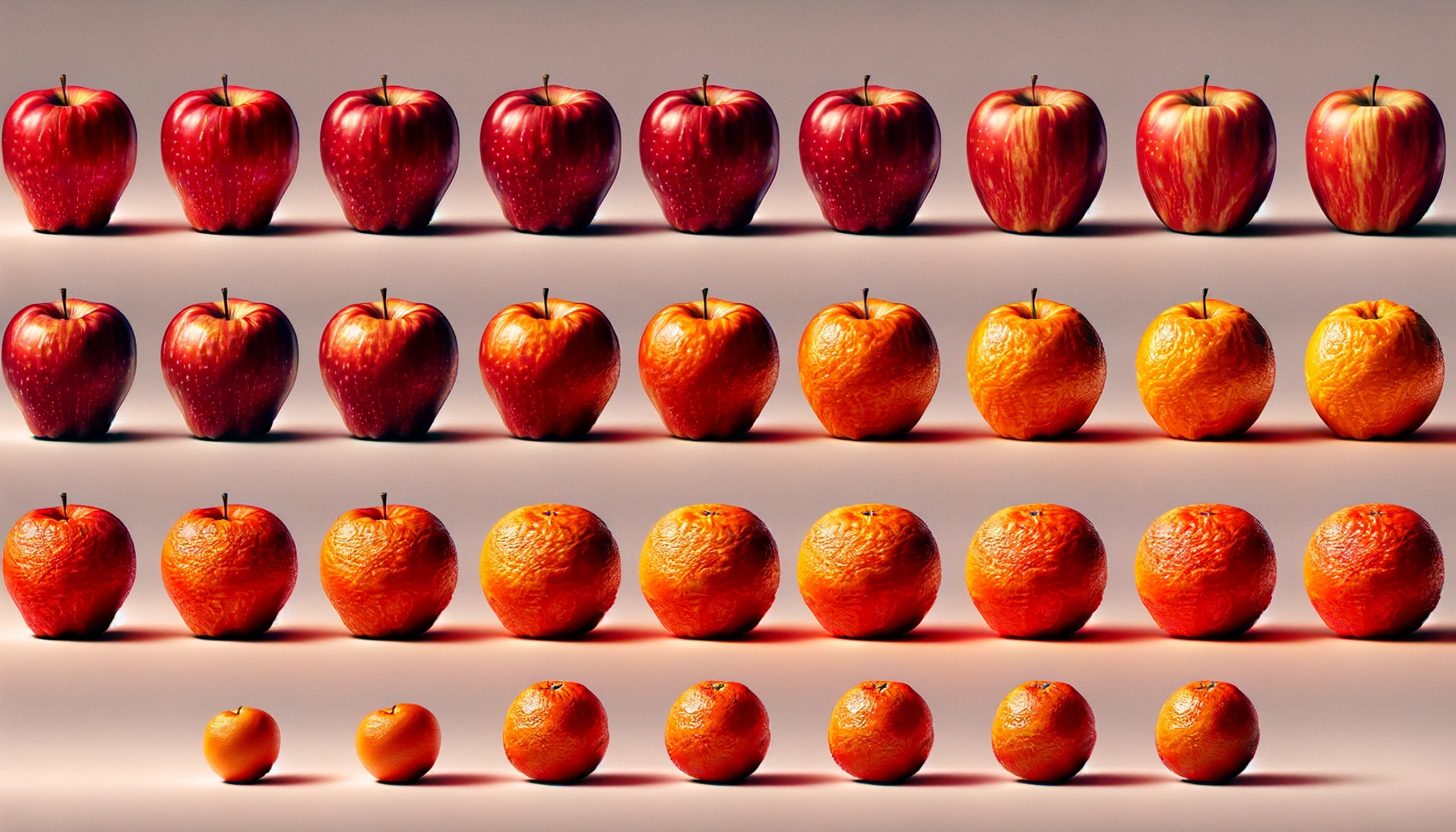

Or between an apple and an orange:

Revealing some understanding of what is apple-ness and orange-ness in the latent space of the model, but also that this can be a relatively continuous band between these two centers where it’s possible to interpolate the apple between the two. It’s just as revealing that we are able to interpret this image: we see an apple, but we also see it obtain the texture and increasingly the form of an orange. It suggests that we ourselves have the ability to perceive apple-ness and orange-ness in an image and that there is a relatively smooth band between them. It’s a worthwhile exercise to spend some time staring at the intermediate apple-oranges and try to understand what about them, in the field of perception, give them apple-ness and orange-ness respectively:

The different features of these appleoranges: surface texture, shape, appearance of a stem, color, all combine to create these uncanny hybrid fruits. They’re not a simple blend of apple and orange, but rather hybrids of what representations give one the ability to perceive apple or orange. The model does so in a game with what is known about representations in image, in some way it’s almost as if it’s as much hacking our own visual perceptual system in order to create something that’s recognizable as both apple and orange. It seems to access just the right features and blend them, while maintaining the constraints of light and shadow to generate the hybrids. We might call these elements that the model is working with “features” though it would appear to me that these underlying stylistic elements that make up the recognizability of various objects are as much the surface features as they are the underlying constructs that endow a form with its visual recognizability. In all of these examples, the constructs intermingle to create relatively novel and bizarre transformations of the familiar construct of an apple.

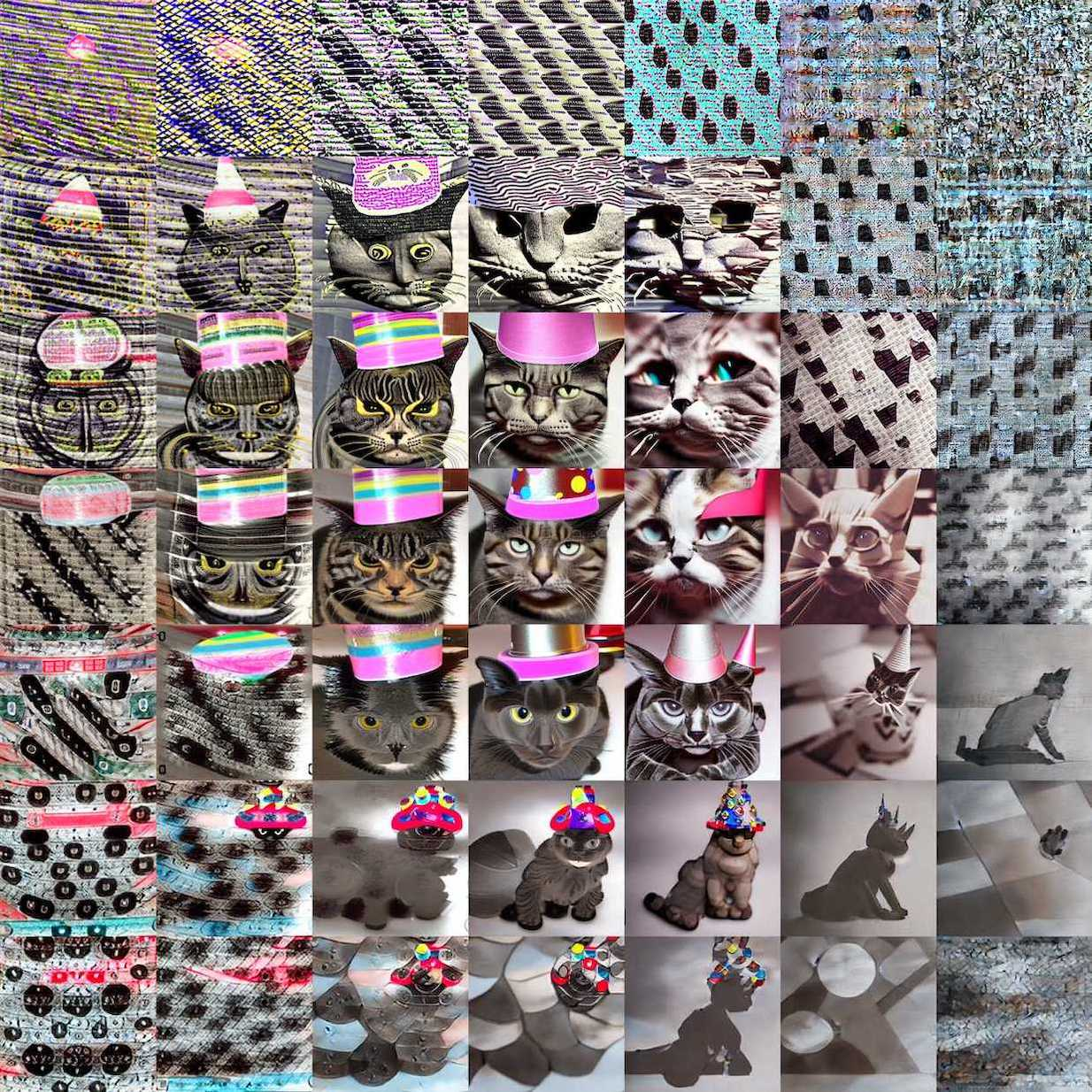

The latent space surrounding apple might be outside anything that appears familiar, as this sampling indicates, showing there are like far more strange, unfamiliar constructs that emerge in latent space beyond the margins of the familiar (apple).

Here we observe a whole complex network of constructs intermingling. Some are recognizable, like the watermelon (watermelon-fruit proximity construct) or the brain shape applied to an apple form. We see pears, but we also see delightful and at times disturbing transformations applied to the apple. In my view, some of these forms are truly novel in that looking at them is like looking at something I’ve never seen before. It exists on the margins of my perceptive ability, well outside the familiar constructs I’ve come to expect in the world. Looking at some of these shapes is like seeing something truly alien. It’s form that lies well outside any familiar constructs I know.

For a more detailed dive on a similar view, check out:

An “island” of cats in party hats, surrounded by less recognizable images. Referring to the images on the edge, the authors ask:

What are all these things? In a sense, words fail us. They’re things on the shores of interconcept space, where human experience has not (yet) taken us, and for which human language has not been developed.

Stephen Wolfram (2023), “Generative AI Space and the Mental Imagery of Alien Minds,” Stephen Wolfram Writings. generative-ai-space-and-the-mental-imagery-of-alien-minds.